History

With the arrival of World War 2, an increase in secret radio communications caused countries on both sides of the War to start using more complex methods of cryptography. Here we are going to focus on one of the most famous methods, Enigma, a German cipher machine.

The machine was developed by Arthur Scherbius in 1918 and was based on the rotor-based cipher machine that was being developed simultaneously in many countries towards the end of World War 1. Prior to World War 2, it was used globally by both military and commercial communications around the world. The German armed forces started using it in 1926.

Design

The machine used three rotating disks (from a selection of five), lamps, spindles and a keyboard. Each letter of the plaintext is entered into the machine and goes through all three rotors and then back again to the other side. The board lights up to show the outputted letter that has been encrypted, and the first rotor then rotates to the next position so that even if the same letter is inputted there will be a different outcome. Once the rotor has rotated through all 26 positions, the second rotor starts to turn, and when it has also gone through 26 positions then the third does the same. The letter passes through the plugboard twice, after being inputted and before being outputted, each time transposing the letter with its matching pair.

In order to decrypt the encrypted text, only information about the starting position, order of the three rotors being used and the positions of the plugs in the board are needed. The text is then simply needed to be typed back into the machine. Because the reflector in the machine that makes the letter pass through the rotors twice, decrypting the text uses the same method as encrypting but in reverse. This machine was so complex that there were over 17,000 different combinations before the process repeats from the starting position and almost 160 quintillion settings. This led many people to believe that the Enigma machine could not be broken.

Breaking Enigma

Conscious of the possibility of a second war, the Polish Cipher Bureau started work on breaking the Enigma cipher in 1930 using information on the commercial Enigma machine (an previous version of the WW2 Enigma machine that had three set rotors) and some messages that had been intercepted. In 1932, Marian Rejwski managed to determine how the internal wiring of the Enigma was set up after finding that the first three letters of a message were identical to the next three. His colleague, Henryk Zygalski, created the Zygalski sheets that exploited a weakness in the German procedures caused by the double enciphering of the rotors. The version of Enigma that was used by the German military required checking thousands of possible daily keys until the encrypted message was broken. To overcome this problem, they built the “bomba kryptologiczna” to exploit the vulnerability mechanically and cut down the work needed to check the keys. Two additional rotors were introduced to the Enigma machine in December 1938 so that three rotors could be selected from a set of five. This significantly increased the amount of work needed to find the daily key. With the impending threat of war, Poland decided to share its progress of cracking the Enigma machine with the French and British.

The machine was developed by Arthur Scherbius in 1918 and was based on the rotor-based cipher machine that was being developed simultaneously in many countries towards the end of World War 1. Prior to World War 2, it was used globally by both military and commercial communications around the world. The German armed forces started using it in 1926.

Design

The machine used three rotating disks (from a selection of five), lamps, spindles and a keyboard. Each letter of the plaintext is entered into the machine and goes through all three rotors and then back again to the other side. The board lights up to show the outputted letter that has been encrypted, and the first rotor then rotates to the next position so that even if the same letter is inputted there will be a different outcome. Once the rotor has rotated through all 26 positions, the second rotor starts to turn, and when it has also gone through 26 positions then the third does the same. The letter passes through the plugboard twice, after being inputted and before being outputted, each time transposing the letter with its matching pair.

In order to decrypt the encrypted text, only information about the starting position, order of the three rotors being used and the positions of the plugs in the board are needed. The text is then simply needed to be typed back into the machine. Because the reflector in the machine that makes the letter pass through the rotors twice, decrypting the text uses the same method as encrypting but in reverse. This machine was so complex that there were over 17,000 different combinations before the process repeats from the starting position and almost 160 quintillion settings. This led many people to believe that the Enigma machine could not be broken.

Breaking Enigma

Conscious of the possibility of a second war, the Polish Cipher Bureau started work on breaking the Enigma cipher in 1930 using information on the commercial Enigma machine (an previous version of the WW2 Enigma machine that had three set rotors) and some messages that had been intercepted. In 1932, Marian Rejwski managed to determine how the internal wiring of the Enigma was set up after finding that the first three letters of a message were identical to the next three. His colleague, Henryk Zygalski, created the Zygalski sheets that exploited a weakness in the German procedures caused by the double enciphering of the rotors. The version of Enigma that was used by the German military required checking thousands of possible daily keys until the encrypted message was broken. To overcome this problem, they built the “bomba kryptologiczna” to exploit the vulnerability mechanically and cut down the work needed to check the keys. Two additional rotors were introduced to the Enigma machine in December 1938 so that three rotors could be selected from a set of five. This significantly increased the amount of work needed to find the daily key. With the impending threat of war, Poland decided to share its progress of cracking the Enigma machine with the French and British.

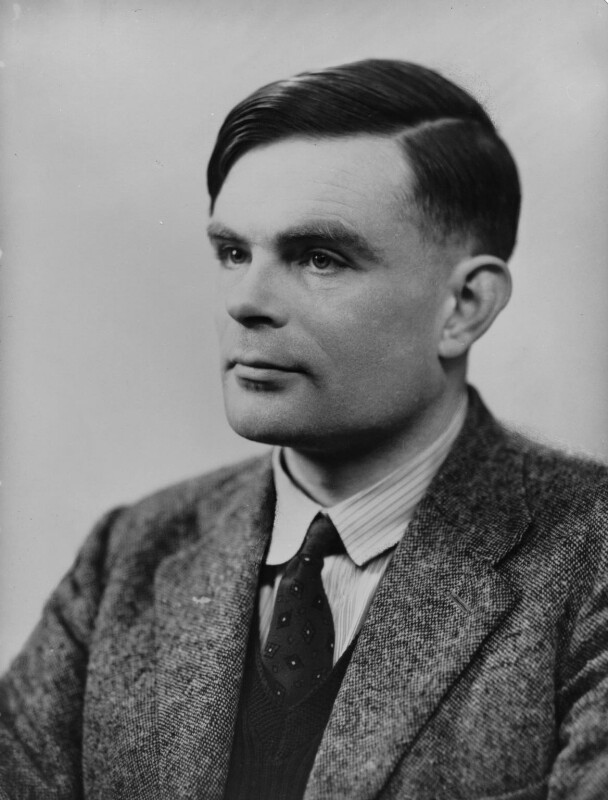

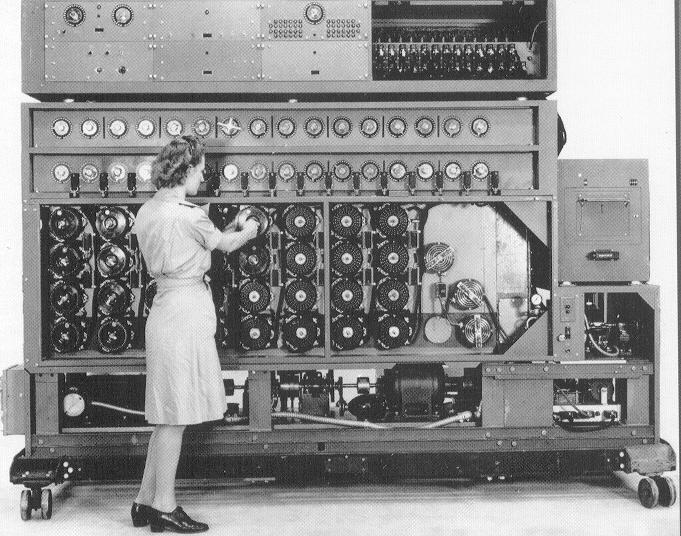

The British set up the Enigma Research Section at Bletchley Park, where Dilly Knox and Tony Kendrick worked and were later joined by Alan Turing, Gordon Welchman and Peter Twinn. In 1939 they built their own machine, called “bombe”, which was developed from the bomba kryptologiczna. It was designed by Alan Turing and was significant improvements were made in 1940 by Gordon Welchman. The bombe was built to find daily keys, which set of rotors were in use, the message key and the wirings of the plugboard for intercepted messages. The machine checked the different possible settings of the Enigma machine by using row upon row of rotors that would spin in order to test them.

The British set up the Enigma Research Section at Bletchley Park, where Dilly Knox and Tony Kendrick worked and were later joined by Alan Turing, Gordon Welchman and Peter Twinn. In 1939 they built their own machine, called “bombe”, which was developed from the bomba kryptologiczna. It was designed by Alan Turing and was significant improvements were made in 1940 by Gordon Welchman. The bombe was built to find daily keys, which set of rotors were in use, the message key and the wirings of the plugboard for intercepted messages. The machine checked the different possible settings of the Enigma machine by using row upon row of rotors that would spin in order to test them.

The first bombe built on 18 March 1940 was named “Victory” and was based on Turing's original design. On 26th April 1940, a German trawler (Schiff 26, the Polares) was captured and some Enigma keys for 23rd to 26th April were obtained. By May and June 1940, Bletchley was able to break six days of intercepted naval messages from 22nd to 27th April 1940. This was the first time during the War that Kriegsmarine (the German navy) messages were broken. However, this did not help with the decrypting of new messages as the future settings of the Enigma machines were unknown and Turing’s original bombe was not efficient enough to resolve this. This was due to the impractically long cribs needed to reduce the number of settings that needed to be checked. Gordon Welchman’s improvement to the bombe was an attachment of a diagonal board to the second bombe built, “Agnus dei”, that increased the bombe's effectiveness. The same improvement was made to Victory and both machines were able to decrypt the majority of intercepted messages during 1940.

Other Rotor-Based Machines

It is worth mentioning that the German Enigma machine was not the only one of its kind at that time. Examples of other machines are Poland’s Lacida, Japan’s Type B Cipher Machine (a.k.a PURPLE), Britain’s Typex and America’s SIGABA. These were all rotor-based machines used in World War 2 and had varying levels of security. The Typex was even still used in the 1970s by the New Zealand Military.

Written by Kendal

The first bombe built on 18 March 1940 was named “Victory” and was based on Turing's original design. On 26th April 1940, a German trawler (Schiff 26, the Polares) was captured and some Enigma keys for 23rd to 26th April were obtained. By May and June 1940, Bletchley was able to break six days of intercepted naval messages from 22nd to 27th April 1940. This was the first time during the War that Kriegsmarine (the German navy) messages were broken. However, this did not help with the decrypting of new messages as the future settings of the Enigma machines were unknown and Turing’s original bombe was not efficient enough to resolve this. This was due to the impractically long cribs needed to reduce the number of settings that needed to be checked. Gordon Welchman’s improvement to the bombe was an attachment of a diagonal board to the second bombe built, “Agnus dei”, that increased the bombe's effectiveness. The same improvement was made to Victory and both machines were able to decrypt the majority of intercepted messages during 1940.

Other Rotor-Based Machines

It is worth mentioning that the German Enigma machine was not the only one of its kind at that time. Examples of other machines are Poland’s Lacida, Japan’s Type B Cipher Machine (a.k.a PURPLE), Britain’s Typex and America’s SIGABA. These were all rotor-based machines used in World War 2 and had varying levels of security. The Typex was even still used in the 1970s by the New Zealand Military.

Written by Kendal